I am at the hospital. A woman wearing a hijab motions for me to sit next to her.

"Where you from?" she stares up with wonder, as if she's never seen anyone so tall before. If I ever thought the frequent statement you're tall from strangers back in the States was annoying, I've come to accept that being nearly six feet in India makes me quite a giant of a superstar. Oftentimes I am wary of this attention as it can mean photo after cell phone photo with teenage boys and entire extended families. But right now, it's just a woman and a man who want to meet me, so I sit.

"U.S." I say.

"I am Muslim," she says confidently, a statement I doubt I've ever heard so forthrightly back home since before our country became full of terror. It's not so politically correct to talk about religion upon first acquaintance in America. "What are you?" another bewildering question asked with as much ease as the common Californian conversation starter, what's your star sign?

Before I can answer she guesses, "Christian?"

Yes, I nod. It's easiest to go with her assumption.

The guy next to her seems to dispute something in Hindi. She then asks, "America have Muslims?"

"Yes, of course," I nod. I can't help but think how amazing it is that she genuinely has no idea about our country's media enhanced struggle with radical jihadists, terror, the accompanying prejudice, and fear. She turns back to him with a look of defiance.

It seems her English has run out, so we sit next to each other in awkward silence. The two of them continue to stare me down with no shame, in a way that only people who live in cultures where such behavior is socially acceptable can get away with. I try to ignore the uncomfortable feeling of scrutiny. Two nurses bustle past, and my thoughts return to the task at hand.

***

At the boat dock in transit to the hospital

Working our way slowly north along the western coast of India, we have landed in Fort Kochi, capital of the South Indian spice trade. Westerners historically wanted in on the wealth potential of this rich spice hub. The Portuguese were first to swoop in around 1503. The Dutch and British were not long to follow, leaving behind old-school colonial type buildings and Christianity.

But instead of exploring the remains of Catholic churches and working spice warehouses, I am sitting inside the government hospital waiting for my travel partner. Since this morning, his ear has been dripping blood.

***

The streets of Fort Kochi

Random garbage heap in Fort Kochi, not an atypical sight pretty much everywhere in India

In order to arrive here, we weave our way by foot through speeding tuk tuks and uneven cracked cement slabs pretending to be a sidewalk. It's humid, loud, and dirty. Just outside the Ernakulam hospital gates, a uniformed girl and I make eye contact. Before I know it, she beelines straight for me, never breaking her gaze. Grabbing my wrist, she yanks me right around the corner and inside the gates.

Here sit about fifty other girls wearing blue saris — nurses in training. They are all staring, wide-eyed, as if they've never seen a white girl before. The girl who discovered me begins to giggle. Pretty soon they're all laughing. At me.

I smile, amused to suddenly be on display like a science project. Gesturing to my friend, I ask where to go for a problem with the ear. "Casualty" she says, pointing and bobbling her head from left to right.

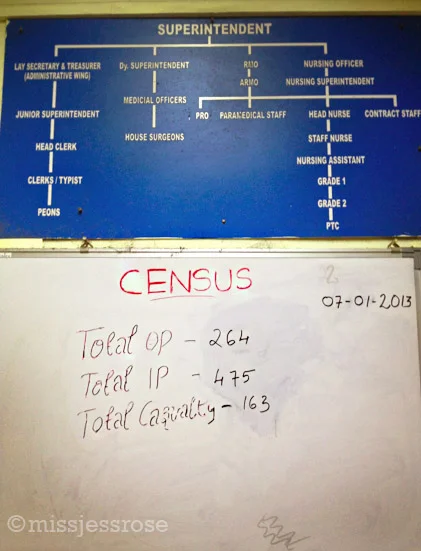

The so called Casualty ward of the hospital is crowded, open-aired, and worn beyond anything I could ever imagine back home in the U.S. Families stand crowding what appears to be a reception desk where three administrators sit behind a chain-link barrier trying to process the masses. People elbow each other jockeying to get closer to the front, some waving slips of paper, others chattering away on cell phones. A cluster of people block the entrance to the ICU where doctors appear to be treating patients. India's burgeoning population feels all too real here. The chaos, the crowd, the grime is so foreign from what I know as medical care, for a moment I lose track of why we are here.

So I sit, and wait. And have a chat with a muslim.

***

Let the wait begin... (Photo: C. Paine)

An impressive crowd waits to receive medical attention (Photo: C. Paine)

It takes us awhile to figure out how this works, and even when we do, I know we receive special attention since it's obvious we are foreigners.

We pay a mere two rupees, all of about ten cents, and sign a roster. Then shove our way into the room filled with mothers clutching crippled children, old people hunched and coughing, people who look to be much worse off than us.

But we are American. We do things differently. We are — how might I say this delicately? — entitled?

Without trying too hard, the crowd seems to part enough for us to move to the front where we are seen by a doctor who prescribes antibiotics for the ear infection in all of two minutes time.

***

A very brief ear exam is conducted by a doctor in a communal room (Photo: C. Paine)

At last, picking up antibiotics from the medicine dispensary next door (Photo: C. Paine)

This is not the first time on our trip that I will feel deep guilt for being born as I am, for being privileged. Why do I have the fortune to live life as a giver and not a beggar? This question haunts me every time I turn away from a cripple with polio crawling the street asking for rupees, or a tattered looking gypsy mother carrying an impossibly dirty baby pulling at my wrist asking for change.

To travel deeply in India is to stare poverty in the face. To begin to understand the tip of this suffering is to be brave enough not to look away with shame.

India is full of impossibly unfair realities, all more visible than any other place I've ever been. Suffering is everywhere — constantly — on the stoop of my hotel, sitting next to me on the train, here in the desperately crowded hospital waiting room.

Seeing humans in such downtrodden states breaks apart my understanding of what I now see clearly as my own good fortune. I am ashamed of everything I take for granted. I think about all the people I know in Los Angeles with their therapists and their Xanax. I think about how they have no idea what it truly means to suffer, at least not the way masses of people in other parts of the world do. The people waiting here at the hospital don't have time for the kinds of problems most Americans I know have. The people here in India are too busy trying to survive.

***

But despite this, I love India because aside from suffering, India is full of life.

People here have heart. They feel vital and alive with wonder, happiness, and love. Sickness and death are just natural parts of a spectrum. There's no pre-packaged sterilized false reality here. Everything is raw, and unavoidably real.

“That’s how we keep this crazy place together –– with the heart. Two hundred languages, and a billion people. India is the heart. It’s the heart that keeps us together. There’s no place with people like [Indian] people. There’s no heart like the Indian heart.”